Teams that move quickly often encounter challenges with code management including merge conflicts, incompatible implementations, and outdated documentation. The right branching strategy can help accelerate your team with minimal effort.

Picking a workflow

Before moving forward with a workflow you should decide whether it’s right for your team. Ask whether a workflow scales well with your team size, does it introduce harder challenges, does it impose too many restrictions on contributors, etc. Don’t just jump in with a workflow because that can leave your team in a mess.

Feature Branch

In this workflow, each addition (feature, bug fix, etc) is developed in a separate branch based on a shared main branch. This encapsulation ensures a minimal amount of conflict, collaboration, and code review.

It ensures minimal conflict by allowing conflicts to emerge only at the moment of merging the branch or during a rebase (when you're bringing a branch up to speed on new changes to the base branch). This allows the conflict to happen in a controlled environment without affecting stable main branches.

It ensures code review and collaboration through the use of merge requests (aka pull requests). Merge requests allow discussions to happen around a specific branch before it's merged. During these discussions reviewers can request code changes, help implement difficult features, suggest better implementations, or provide valuable insight in general. A merge request doesn't automatically translate to a ready-to-merge branch.

You can probably notice this workflow in almost every project in the wild. It's composable and other workflows have it at their core.

This flow is best suited for smaller projects with a quick release cycle that consists of a minimal number of contributors. It’s also prone to critical bugs so testing should be heavily relied upon. Most workflows extend this workflow in some way.

In the CI/CD world a “preview” environment could be created for each merge request, and the production environment can be based on the main branch. This is too much for smaller projects though so you may end up with only the production environment. In this case you should rely on automated testing and code quality control pipelines.

Feature flags are worth mentioning because they allow us to ship continuously without introducing incomplete features or critical bugs to the users. They require some setup of their own and come with their own set of challenges in but their value is totally worth it.

Gitflow

Gitflow involves heavy usage of feature branches and multiple main branches (keyword here being multiple). It was published by Vincent Driessen on his blog in 2010.

This workflow can be thought of as a heavy mutation of the Feature Branch Workflow as it doesn't introduce complexity through new concepts, but rather assigns specific roles to branches. It is one of the most complicated ones, and therefore the choice for using it should be studied carefully as it may be overkill.

Gitflow consists of two main branches: master and develop. The master branch always contains production-ready code. develop on the other hand contains the latest delivered development changes for the next release. This is where beta, nightly, or similar builds are created from.

This is not all of it though. Gitflow assigns “supporting” roles to branches such as release branches, hotfix, and feature. Each feature branch is branched off from develop and must be merged back into develop. The merge must not be a fast-forward to not lose info about the existence of feature branches.

Release branches are branched off from develop and can be merged back into develop and master. A release branch is created when the code on develop “almost reflects the desired state of a new release”. Feature branches that are set to release in later versions are not merged to develop until the current release branch is created.

A release branch may receive code changes that are not anywhere else such as bug fixes related to that release. When a release branch is ready to become a “real release” it is merged into master and tagged with a release number. The changes on the release branch must then be merged back into develop.

Hot fixes are branched off from the most recent master and merged back into master and develop. If a release branch exists then the fix needs to be merged into it instead of develop.

Vincent documented this approach 13 years ago when most software was explicitly versioned and teams maintained multiple versions concurrently. He added a note of reflection to the original post 3 years ago, which I quote:

[…] the most popular type of software that is being developed with Git is shifting more towards web apps — at least in my filter bubble. Web apps are typically continuously delivered, not rolled back, and you don't have to support multiple versions of the software running in the wild. […] This is not the class of software that I had in mind when I wrote the blog post 10 years ago.

— Vincent Driessen

That statement still holds true to this day. Web apps are prominent amongst software teams, and they’re usually released in cycles of weeks (sprints) or even multiple times a day.

The decision for Gitflow should be considered with care provided the overhead it introduces. It requires relatively advanced knowledge of git and the flow itself, is not easily enforced with hooks or GUI tools, and is not easy to adopt.

GitHub Flow & GitLab Flow

Gitflow was too complicated for the fast-moving GitHub team. It has its strengths and weaknesses, but one of the bigger issues the developers at GitHub faced was that they deployed multiple times a day. And while Gitflow is based on the idea of “release”, its definition of “release” is too constraining for teams to quickly and rapidly move with.

GitHub Flow was created to provide a simpler approach that allows GUI users and developers who may not be comfortable with the system to easily follow along. It's based on several principles:

- Anything in the master branch is deployable

- Create descriptive branches off of master

- Push to named branches constantly

- Open a pull request at any time

- Merge only after pull request review

- Deploy immediately after review

GitLab flow is identical with the application of merge requests and issues for progress tracking. This approach is fairly simple, introduces no git management overhead, and can be paired with Git Worktrees.

You can link merge requests to issues, close issues with specific commits, and more. The approach utilises GitLab features heavily and doesn't really differ that much from GitHub flow.

Both workflows can benefit from, and are usually paired with, environment branches.

Trunk-based development

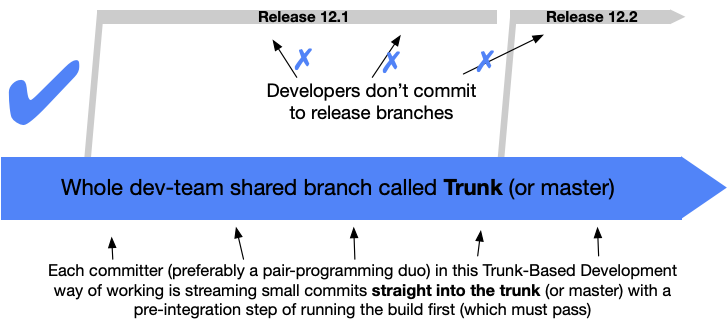

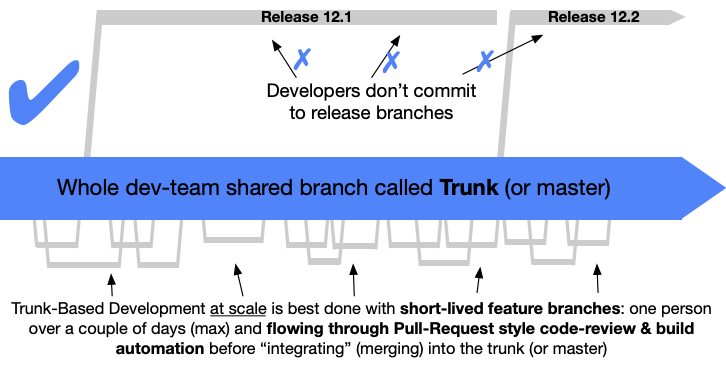

Trunk based development is similar to other approaches but describes a workflow in which developers commit directly to the trunk (master) branch.

One-off release branches, if needed, can be created from the trunk just in time for a new release and never touched again once the release is published.

Committing directly to master obviously doesn't scale and so the usage of short-lived feature branches can be incorporated into this workflow for build checking on CI/CD and code review. This scaled version can be thought of as a simplified version of Gitflow.

Environment Branches

Teams often require a different environment for testing things out manually without releasing a new production version. This is especially useful when experimenting stuff that require client/manager approval.

With this approach you may encounter 4 environments, represented by corresponding branches as follows:

- Dev: the most unstable environment, usually local only and not replicated on a server but can be nonetheless.

- QA: an environment specifically made for quality assurance and bug reporting testing. This is the main source of bug reports and change requests.

- Staging (pre-prod): the environment that most closely resembles the production environment. This environment is used for client and manager review, and is recommended to keep as stable as production. This is the release candidate.

- Production (master): the current released version of the software, accessible to end-users.

There is also data environments that correspond to these environments. Each data source usually supports a specific environment. For example, the databases supporting dev are usually the same as the ones supporting the QA environment.

Staging has a separate data source, and so does production. Production and staging are not recommended to have the same data source especially for software that relies on user-generated content as clients and managers could test with dummy data that you may not want users to see.

This strategy of assigning environment roles to branches works best with simple branching workflows such as the Feature Branch, GitLab, and GitHub workflows, and allows fast moving teams more security and control over their releases. It's best suited for teams who wish to work fast and release fast with controlled environments.

Release Branches

Release branches, as mentioned in the Gitflow workflow, are branches specific to a release. For example, you may have branch 0.0.1, 0.0.2, etc.

Release branches are not specific to Gitflow though, and can be easily paired with other branching methods. It works best for teams who have specific release dates, teams who wish to maintain multiple versions of their software, and teams who work with explicit app versions.

With this approach, a release is usually created from the main branch in the same fashion that Trunk-based development uses

Footnote

Each workflow has its own set of benefits and challenges, and the choice eventually comes down to which flow best fits your team. Always try to minimize the friction between developers, keep feature and bug-fix branches as short-lived as possible, and integrate CI/CD into your workflow to make things easier for yourself.

Written by Nabil Tharwat

Nabil Tharwat is a software engineer and mentor who's super in love with all things accessibility and performance. He's host of The Weekly Noob podcast and his content has reached thousands of people around the world.